By Seema Nanda

It was 1998. I lived in the suburbs of Houston with my parents. In October, my dad and I went up to Philadelphia together. He bought me a purple bathrobe and pajamas with sheep on them. He dropped me off with a hapless look on his face.

At that point, I weighed eighty-eight pounds. Something had really gone wrong in my life. I thought, “What am I doing here?” Anxiety gnawed at my nerves. I had trouble falling asleep. When I did, I ground my teeth. My mind raced. I couldn’t read anything, which was the worst blow.

Living in an anorectic body is horribly uncomfortable. It hurt to lie down. It hurt to walk. There was hardly any flesh on me to act as cushion. My skin stretched across my pelvic bones, taut, like a drum. When I couldn’t sleep, I would trace with my fingertips the ridges of bone that rose up from my body. My face was ashen.

Ostensibly, I was there at Renfrew to untangle this mess. I went along with the program, but I didn’t understand it. I simply ate everything they told me to eat. At Renfrew, we ate three meals a day and three snacks a day. If any of us was unable to complete our meal plan, there was a disgusting, thick drink at the end of the day to compensate. When I wasn’t eating, I talked about my feelings.

My family hadn’t raised me to talk about feelings. My mother, who came from a stoic military family, kept hers in a jar on top of the refrigerator. I had wrestled with my own discontent and disconnection since the age of fifteen. There I was, at 21, still trying. Things were worse now because not only was I unhappy, I was dangerously underweight.

I had lost any ability to communicate. I felt no power over my own life or my decisions. My boyfriend had moved to London to do fieldwork. I couldn’t bear his absence. My family was a mess, as usual. So, I had decided to eat very little each day. I didn’t know any other way of coping.

In the dining hall, we enacted our eating disorders. In the line to get food, I heard apologies non-stop. If someone barely nudged me, she would apologize. In the dining room, we would push our food around in little loops on their plates. Others would hide it in their napkins to throw out later.

The bulimics and anorexics had their own sets of behaviors. The bulimics wore their anger like armor. They spoke up and didn’t exhibit visible physical signs of their condition, unless I had a mind to peek into their mouths and took a look at their teeth.

The anorexics, well, we were a different story! We accommodated everyone and treaded lightly. Our skinny bodies buckled under invisible burdens.

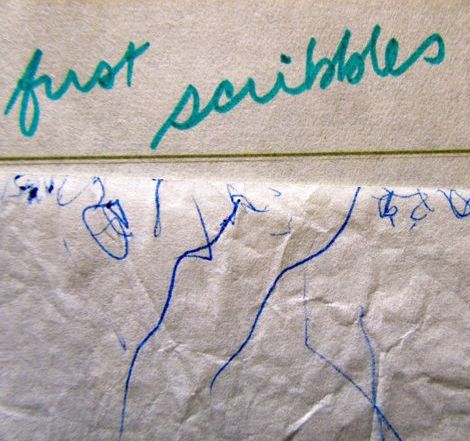

Other than eating, there was therapy. We had group therapy once or twice a day. We had art therapy. We had individual therapy. We had therapy inside and we had therapy outside. We had therapy for hours every goddamned day.

The staff reminded me of the Secret Service. If you broke a rule, of which there were many, the entire staff knew. Throughout the day, various members of the staff would ask you what happened and why. The whole system gave me the creeps. No one had paid such careful attention to me in my life besides my mother! Who the hell were these people?

My 22nd birthday arrived while I was there. I had a friend nearby at Penn Law School and another who had just relocated from Houston to New Jersey. I made plans for them to bust me out for my birthday. The staff had a procedure in place for having dinner out with family or friends. They neglected to tell me I had to dine at a restaurant near the treatment facility, so we went to a restaurant in Philadelphia.

As my birthday approached, I lobbied for a dinner pass. I handwrote a few notes on thick, cream-colored stationery to two members of the staff. They had stipulated that I should weigh 100 lbs. by the time my birthday came. I told them I had never weighed 100 lbs. in my life! My mother hit that mark only after giving birth to my brother. I explained it wasn’t because I didn’t want to, but that it just hadn’t transpired yet.

I won a dinner pass for my birthday! I was elated! I counted down the days until the big day. My parents sent me red roses and I received many cards and gifts from family and friends.

Shachi, a friend who had moved to New Jersey, came and picked me up in her car. She brought me a new pair of jeans from Old Navy because I had grown out of mine. Shachi brought along her friend Stephanie and we went to the restaurant.

Amy, the law student, met us there. It was located in the basement of a building. The room was long and had exposed brick walls. I was nervous and scared, but Amy sat next to me and held my hand. It had been three weeks since I had eaten a non-Renfrew meal. There was no Secret Service staff at the restaurant. I felt strangely unmoored.

I left for the bathroom. When I returned, all the lights were off. Candles at each table lit up the darkness. Everyone sang to me! I felt so special. A waiter brought in my cake with just one candle. We ate and had a lovely time.

Afterwards, Shachi and Stephanie left. Amy and I went to her friend’s apartment. We were out late by then. Amy told me to call the Renfrew Center. I had broken curfew due to travel time from Renfrew to Philadelphia. I was in trouble! I thought it was odd for someone who just turned 22 to be in trouble, but I kept that to myself.

I went back and went to bed right away. The next day, everyone was talking. Everyone knew I had broken the curfew. My shrink admonished me. My therapist said she was disappointed in me. The staff told me they weren’t my parents.

They said this as if I should understand what they meant by it. Of course they weren’t my parents! My parents didn’t have to be paid to make my life hard. That came free! On the other hand, Barb, one of the other inmates, told me I was her hero.

I told the staff no one had told me where I could eat. It was true. I said I was sorry. Then, I started handing out flowers. Remember the roses my parents had sent me? I handed them out to make amends. In a few days, the whole thing was forgotten. They were touched and surprised. I realized I had caused them to worry for my safety.

Life at Renfrew went back to normal. I ate and I went to therapy and then I ate some more. I hated that damn place. It was the most beautiful setting, but a living hell to experience. The worst of it was the group therapy. Gutting yourself with an audience is unlike anything I have ever experienced.

Ten days later, I got out! When I left the Renfrew Center, I weighed 96 lbs. It had given me a needed push. I soon did weigh 100 lbs. They would have been proud of me. During the course of the next five years, I would be hospitalized twice more, for related reasons. The last time was in 2000. I haven’t been hospitalized since.